By Patricia Hartley

Women were just as important to a household and community hundreds of years ago as they are today but, thanks to laws and social ideas that limited women’s roles and rights, their contributions and names are often lost to history. This makes identifying and tracking our female ancestors particularly challenging.

The United States Federal Census records from 1790 through 1840, for example, give a skewed snapshot of the role of women in those earlier decades of our country. Men were named and clearly labeled as heads of the household, while the women of the family were simply check marks in the “female” column.

Beginning in 1850, women were named in the census and more vital records became available but, even after this time, determining a maiden name, line of work or parentage can be difficult.

To uncover your female ancestors’ lives, you’re going to have to work harder, dig deeper and be more creative. Let’s look at some ways to overcome these challenges and discover more details about the women in our family trees.

The Usual Suspects: Using Census, Marriage, and Birth Records to Research the Women in Your Tree

Census records, marriage records, and (if available) birth certificates, usually offer great clues for at least the first names of female ancestors, or perhaps even maiden names and the names of parents.

Of course, these records are only as reliable as the person providing and recording the information, so the information gleaned should be used with caution and as contributing facts to your larger body of research.

Because the information on a birth certificate or birth record is usually provided by the mother, parent’s names are most often accurate. However, most states didn’t start keeping birth records until the early 20th century, so they aren’t available for many of our older female ancestors.

Marriage records can provide a wealth of information and often predate birth records. Depending on a particular county’s record keeping method, you may come upon a marriage license that includes not only the bride and groom’s full names, but also the names of their parents and a notation of any previous marriages.

Tip: If a bride is a widow, some marriage records will list her last name as that of her deceased spouse rather than her maiden name; this simple misunderstanding could easily send your research spiraling into a fruitless search, so proceed with caution.

20 Billion Genealogy Records Are Free for 2 WeeksGet two full weeks of free access to more than 20 billion genealogy records right now. You’ll also gain access to the MyHeritage discoveries tool that locates information about your ancestors automatically when you upload or create a tree. What will you discover about your family’s past?

Older marriage records usually list only the bride, groom, officiant, and marriage date – especially if they’ve been transcribed. Locating the original records will often offer surprise clues in the form of permission to wed or authorization that the bride or groom was of age.

For example, you may find notes like “Bride’s brother John Jones attests to her age,” or “Absolom Thomas gave permission for his daughter to wed.” These nuggets of information not only add new limbs to your tree but provide further proof of your female ancestor’s maiden name!

Check the source of an index for where the original record is located and then access it if you can. Do this for every index and transcription you use, not just marriage records, since clues about your female relatives are likely hiding in these documents.

As with any individual listed in a census, when searching for information about the women in your family, the best practice is always to review an actual census image rather than just a transcription or a single record as well.

In addition to the names and ages (even that check mark under the “female” column can give you a clue to the age range of your female ancestor), a census image often reveals valuable clues in the listings of neighbors, households, birth states, relationships, etc. Be sure you’ve taken into account every clue each census and special schedule offers before moving on to the next in search of your elusive female predecessor.

But what happens when you’ve exhaustively searched marriage, birth and census records and are still stumped? Don’t give up yet! There are still many not-so-obvious sources to explore.

Lesser-Used Options for Locating the Ladies in Old Records

Church, Synagogue and Other Religious Records

Thanks to some very diligent church clerks and parish secretaries, today’s genealogists have access to a plethora of vital information about both our male and female ancestors – sometimes reaching as far back as the 17th or 18th century. Houses of worship kept records, in fact, long before the state did in many locations.

Depending on your family member’s religion, house of worship records may contain documentation of everything from your female ancestor’s birth, to her marriage, to her children’s births to her last rites, all of which can be helpful in your quest for answers. Ceremonies like a baptism, bat mitzvah or confirmation may also hold vital clues.

Churches that baptize in infancy or childhood will usually record the child’s parents and perhaps even sponsors or godparents as well. Marriages and deaths recorded by the congregation may also offer more details than civil records.

Church minutes and rosters also hold valuable clues since women often played active roles in these institutions. An 1888 list of members of Providence Baptist Church in Forrest County, Mississippi, for example, includes a notation that “M. A. Bryant changed by marriage to Hamilton.”

Church records can be found in both small archives and large site alike. Look for them by collection. If you have trouble locating these records, try some location research to determine what house of worship your ancestors may have attended and then contact the institution directly. Or, if they are no longer in existence, contact the local historical society for help.

You may want to read Jewish Synagogue Records and Church Records in the U.S., both from FamilySearch, for more help.

Newspapers

Newspapers can be a great resource for information about female ancestors. In addition to being beautifully written tributes that provide insight into a person’s reputation, personality, or standing in the community (“A Mother of Israel Has Gone To Her Reward” is one title that comes to mind), early obituaries can offer wonderful details about an individual’s family history.

Society columns or special sections devoted to news from a particular region of a community are especially helpful with tracking the lives of ladies as well. This passage, “Mr. and Mrs. Gilbert McNatt visited the latter’s parents, Mr. and Mrs. J. R. Halcomb, last Saturday and Sunday” [excerpted from the Franklin County Times, Russellville, Alabama, Thursday, 23 June 1910, page 4, Newspapers.com], provides the maiden name of Mrs. McNatt as well as her father’s name, for example. Marriage notices, births, and other tidbits of news can be just as helpful. Read this article on using society pages for help accessing these records.

Tip: Remember, women were often very active in their communities and in community-building projects. Newspapers are a great way to find this information. For help using newspapers in general see this article.

Cemeteries

Thanks to resources like FindaGrave, we family historians can often review gravestone inscriptions from the comfort of our homes instead of traipsing through an overgrown, isolated cemetery (although most genealogists still enjoy the thrill of uncovering a long-forgotten marker of an ancestor with our bare hands!). Inscriptions vary greatly in the amount of information they offer, but some will actually include the names of a female ancestor’s parents or perhaps her maiden name.

What these online resources don’t offer, though, is context. Knowing exactly where an ancestor’s final resting place is located within the cemetery can offer clues to extended family members. For example, if the plot of Mrs. Florence Gibbons is situated in the Threet family plot and surrounded by generations of Threets, it’s likely that Florence is related somehow to that family, so exploring the possibility that Florence’s maiden name might be Threet is a worthwhile endeavor.

Check out this article for help finding and researching your ancestor’s graves.

Wills and Probate Records

For those lucky enough to have a male ancestor with the foresight to leave a will, these documents can be a gold mine of information that can help identify a female family member. Who doesn’t relish the thrill of finding a will that names all of the deceased’s children, grandchildren, and the names of the male spouses of female daughters?

Unfortunately, many individuals in the 18th and 19th century (and the 20th, for that matter) died intestate, leaving no will and thus forcing their estates to be settled through the probate court.

Probate records offer a wealth of information for family historians because of the volume of documentation that was produced during the process. Household inventories, guardianship paperwork for minor children and dependents, claims against the property owned by the individual, and bonds, letters, or orders sometimes include names of current and previous spouses, siblings, in-laws, neighbors, associates, and other individuals – all of whom can be taken into account during your historical evaluation process as you follow your female line.

You can find wills in many archives and as individual collections on large sites (find out how to locate individual collections here). Another way to find wills is to type the location name (where your ancestor lived) into the FamilySearch wiki and read the entry for clues. USGenWeb is another good free place to start. Many locations have detailed pages with resources.

Tip: Probate records are created by the courts when a person doesn’t leave a will and, often, when they do. FamilySearch estimates that 25 percent of estates were probated for heads of households prior to 1900, so don’t overlook probate records in your research even if you locate a will first.

Biographies and Bibles

Thanks to our predecessors who took the time and made the effort to record the fruits of their genealogical labors, today’s family historians are privy to volumes of published narratives, family trees, and biographical sketches of our ancestors.

The American Genealogical Biographical Index is a great place to find these books, as is the family history section of your local library. Some are even available in a full-text format online. Although it’s tempting to take these accounts as the gospel truth, treat them as you would another person’s online family tree – with caution. Look for solid supporting evidence of the author’s finding in footnotes and endnotes, and consult the original sources if at all possible before adding this information to your own research.

And speaking of the gospel, don’t forget about family Bibles. Even though you may not have inherited your 4th great-grandfather’s Bible, someone else in the family (perhaps a cousin you’ve never met) may have preserved it.

Check out the USGenWeb sites for the counties where your female ancestor may have lived as well as genealogical message boards (like those on Ancestry) for particular locations or family surnames to see if anyone has shared any Bible records that could be relevant to your search. If possible, request copies or digital images of the pages where family history information is recorded to avoid potential errors in transcriptions.

You will also want to look for these books in the Digital Public Library of America and at Internet Archive.

Here are other lesser-used collections you will want to search for your female ancestors:

- Hospital and Asylum Records

- Criminal Records

- Poor House Records

- Pension Records

- Land Records

- and Orphan Train Records

When searching, remember that your female ancestors may have been listed in records by their maiden name, any one of their married names, a nickname, shortened version or variation of their first name, with the surname name of a step-father, with or without a middle name, or as the middle as the first name or by their husband’s name (ie Mrs. James Welch). And, in some records, they are simply not named at all and are instead referred to as the wife of, daughter of, or mother of, but details in such records are still valuable.

Tip: When you cannot locate a women in your tree by name be sure to search for her husband or children instead.

Also be sure to read:

- 7 Little-Used Tricks for Finding That Missing Maiden Name (focuses on special search techniques for researching women)

Researching the women in your tree is going to pose challenges you are less likely to encounter with male relatives. But some hard work and creativity will no doubt lead you to discoveries that are well worth the effort.

For nearly 30 years Patricia Hartley has researched and written about the ancestry and/or descendancy of her personal family lines, those of her extended family and friends, and of historical figures in her community. After earning a B.S. in Professional Writing and English and an M.A. in English from the University of North Alabama in Florence, Alabama, she completed an M.A. in Public Relations/Mass Communications from Kent State University. She’s a member of the Alabama Genealogical Society, Association of Professional Genealogists, National Genealogical Society, International Society of Family History Writers, Tennessee Valley Genealogical Society, Natchez Trace Genealogical Society and the International Institute for Reminiscence and Life Review.

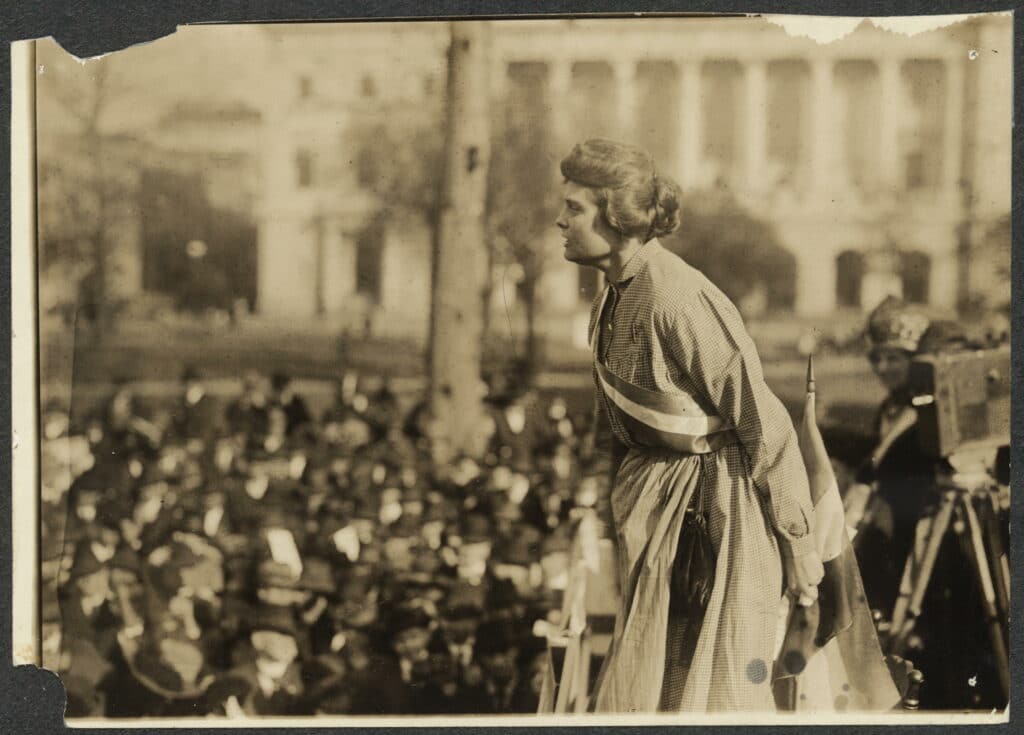

Image: Lucy Branham in Occoquan prison dress. United States, 1919. Library of Congress.

Thanks for this article. I must say, though, that for some reason the women in my line were often listed as head of household, even prior to 1850. Good thing or bad thing? I’m still not sure. In fact, in the 1850 census, I overlooked my gggGrandfather because his name was at the end of the list of people! I’m thinking that it’s possible since he was a manufacturer, he wasn’t at home when the enumerator came on that day and may have turned up after his work day was done, OR the enumerator included those who were present first, and then asked if there was anyone else who normally lived there.

And I agree about religious records. And looking at people in the area. I found a family history for a local family who included scans of church documents that also listed the same gggGrandfather’s ordination in the same church. So never overlook neighbour research.

How can I get a copy of this entire article for my future reference?