|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Do one of the following drone logbook statements accurate describe you?

- “What does the FAA want me to log? I don’t want to get in trouble.”

- “Where do I log it?”

- “Should I do paper or electronic?”

- “I’m confused with all the different terms.”

If any of the above describe you, you are in the right place. We are are going to dive into all of the issues surrounding drone logbooks. This article will be applicable to recreational and commercial drone operators.

There are primarily two types of logbooks: (1) pilot drone logbooks where the pilot logs experience and training and (2) drone aircraft/maintenance logbooks. There are two modes of logbooks: (1) paper and (2) electronic.

Table of Contents of Article

Drone Logbook Law

Logbook Definitions

Before we dive in, let’s discuss some terms that some of you might have heard floating around:

- Acting pilot in command

- Logging pilot in command,

- Remote pilot in command,

- Flight training,

- Ground training,

- Authorized Instructor,

- Pilot,

- Operator, etc.

Brief History of Where the Logbook Definitions Came From

Section 61.51 is the most important section for Part 61 pilots on logbooks and specifically lays out some definitions and the requirements to log that time. These specific terms and requirements were created for manned aircraft pilots to accurately describe their training and experience to meet eligibility requirements to obtain an airmen certificate or added rating. This was how manned aircraft pilots were doing it. Then drones came on the scene.

We had to fit the square in the round hole in September 2014 with the first batch of Section 333 (now called Section 44807) exemptions were released. Some exemptions mentioned that the pilot may log time in accordance with 61.51(b) to show pilot in command (“PIC”) qualifications to operate under the exemption.

Then on August 29th, 2016, Part 101 and Part 107 became law which gave us the term remote pilot in command. That is interesting to note since for a while it was a “must” log until November 2016 where the FAA unilaterally updated 5,000+ exemptions and now they say “may” log in a manner consistent with 61.51(b). All of those exemptions expired. Part 101 was later overruled in 2018 and the FAA withdrew it as a regulation in 2020.

Currently, 61.51 only applies to those not operating under Part 107 or Section 44809. The commercial guys operating under Part 107 don’t have a logbook requirement. The recreational guys flying under 49 USC 44809 don’t have a requirement also.

So, how do we sort this all out when it comes to logging since we have different terms in different parts of the regulations?

How to Make Sense of What to Use in Your Drone Logbook

Part 61 is how you get manned aircraft certificates, while Part 91 is how you lose that manned aircraft certificate (by violating those operating regulations). The Section 333 (now called Section 44807) exemptions adopted the standards in 61.51(b) and then later were changed to say “may.”

Part 107 created this neatly contained part of the regulations which spells out what you need to do to obtain your remote pilot certificate and how to operate under it. You only need to pass a computer-based knowledge exam to fly unmanned aircraft so definitions are not even needed to define knowledge, experience, or training in a logbook to obtain a certificate under Part 107. The definitions only really mattered in a Part 61 & Part 91 situation where training and experience needed to be logged accurately.

Furthermore, 14 CFR 61.8 says, “Any action conducted pursuant to part 107 of this chapter cannot be used to meet the requirements of this part.” You cannot even use the drone time towards obtaining a Part 61 airmen certificate or rating. What a bummer. :(

Moreover, most of the terms are not even accurately being used! If you look carefully at the definitions, you’ll notice that almost all of them 99% of the time cannot be applied to Part 107 remote pilots under a strict reading of the legal definitions. Sure. Everyone will know what you mean but they are not legally accurate usages. But then again, in 107 world, many of these definitions don’t matter. You could call the time flying your Star Wars tie fighter drone “Lord Vader time” because you aren’t using that time to go for a certificate or rating.

Here is a helpful graph of the different definitions, their location, and how a person flying under different parts should treat the definition.

Graph of Different Drone Logbook Terms

|

Term |

Location in the Law | How to treat it. | Definition |

|

Operating Under Part 61 & Part 91 |

|||

|

(Acting) Pilot in command |

14 CFR 1.1 |

This is a term regarding ACTING as PIC. PICs acting as PIC can log it. The reason why there are different terms is because sometimes you can log PIC without being acting PIC. See Logging Pilot-In-Command Time article for AOPA. If you are operating under 107 or 49 USC 44809, this does NOT even apply to you. |

“Pilot in command means the person who: (1) Has final authority and responsibility for the operation and safety of the flight; (2) Has been designated as pilot in command before or during the flight; and (3) Holds the appropriate category, class, and type rating, if appropriate, for the conduct of the flight.” |

|

(Logging) Pilot in Command |

14 CFR 61.51(e) |

Only applicable for sport, recreational, private, commercial, or ATP when rated for the category and class of aircraft. Very rarely will the pilot have the same category and class rating as the unmanned aircraft being flown that is also in compliance with 14 CFR 61.51(j). Even if you get the rare perfect scenario, 14 CFR 61.8 says you can’t even use the PIC time for anything under Part 61 so why bother? | “(e) Logging pilot-in-command flight time. (1) A sport, recreational, private, commercial, or airline transport pilot may log pilot in command flight time for flights” |

|

Solo Flight Time |

14 CFR 61.51(d) |

No one can log this because you can’t get in an unmanned aircraft; otherwise, it wouldn’t be unmanned. I guess a woman could get inside one and it still be unmanned but I don’t know if the FAA will still consider that an unmanned aircraft. 😊 | “(d) Logging of solo flight time. Except for a student pilot performing the duties of pilot in command of an airship requiring more than one pilot flight crewmember, a pilot may log as solo flight time only that flight time when the pilot is the sole occupant of the aircraft.” |

|

Flight Training |

14 CFR 1.1 |

You cannot log this because, once again, you are not “in flight in an aircraft[.]” | “Flight training means that training, other than ground training, received from an authorized instructor in flight in an aircraft” |

|

Ground Training |

14 CFR 1.1 |

Only authorized instructors (see below) can log this in the logbooks of their students. But there are no truly authorized flight instructors for drones. | “Ground training means that training, other than flight training, received from an authorized instructor.” |

|

Authorized instructor |

14 CFR 1.1 |

Here is the problem, ground and flight instructors are “authorized within the limitations of that person’s flight instructor certificate and ratings to train and issue endorsements that are required for” a list of airmen certificates and ratings, but the remote pilot certificate is NOT EVEN ON THE LIST! See 61.215 and 61.193. In other words, ground and flight instructors are not “authorized” to train remote pilots. Sure, flight instructors can train people all day long. It isn’t like the instructor is prohibited from training people, it is just the FAA is not giving its official approval of the competency of the flight instructor to give training to people seeking their remote pilot certificates. But you don’t need the official approval from the FAA for the training because the computer based knowledge exam is what the FAA has officially approved to determine aeronautical knowledge of the remote pilot applicant. | “Authorized instructor means—

(i) A person who holds a ground instructor certificate issued under part 61 of this chapter and is in compliance with §61.217, when conducting ground training in accordance with the privileges and limitations of his or her ground instructor certificate; (ii) A person who holds a flight instructor certificate issued under part 61 of this chapter and is in compliance with §61.197, when conducting ground training or flight training in accordance with the privileges and limitations of his or her flight instructor certificate; or (iii) A person authorized by the Administrator to provide ground training or flight training under part 61, 121, 135, or 142 of this chapter when conducting ground training or flight training in accordance with that authority.” |

|

“Pilot” vs. “Operator” |

The FAA said this very well in now Cancelled Notice 8900.259, “The terms “pilot” and “operator” have historical meanings in aviation, which may have led to some confusion within the UAS community. As defined by the FAA in Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) part 1, § 1.1, the term “operate,” “…with respect to aircraft, means use, cause to use or authorize to use aircraft, for the purpose… of air navigation including the piloting of aircraft, with or without the right of legal control….” This means that an operator is the person or entity responsible for the overall aircraft and that may include a broad range of areas, such as maintenance, general operations, specific procedures, and selecting properly trained and certified flightcrew members to fly the aircraft. The pilot in command (PIC), also defined in § 1.1, is the final authority for an individual flight. Pilots are persons appropriately trained to fly aircraft.” Additionally, the FAA said in the preamble to the small unmanned aircraft rule, “Several commenters noted that using the term “operator” in part 107 could result in confusion. NTSB, ALPA, and TTD pointed out that “operator” is currently used to refer to a business entity and that use of that term to refer to a small UAS pilot would be inconsistent with existing usage. Transport Canada and several other commenters stated that ICAO defines the person manipulating the flight controls of a small UAS as a “remote pilot” and asked the FAA to use this terminology in order to harmonize with ICAO. Transport Canada also noted that: (1) Canada uses the same terminology as ICAO; and (2) calling an airman certificate issued under part 107 an “operator certificate” may lead to confusion with FAA regulations in part 119, which allow a business entity to obtain an operating certificate to transport people and property. ALPA and TTD suggested that the person manipulating the controls of the small UAS should be referred to as a pilot, asserting that this would be consistent with how the word pilot has traditionally been used. As pointed out by the commenters, FAA regulations currently use the term “commercial operator” to refer to a person, other than an air carrier, who engages in the transportation of persons or property for compensation or hire. Commercial operators are issued an “operating certificate” under 14 CFR part 119.67 Because other FAA regulations already use the term “operator” to refer to someone other than a small UAS pilot under part 107, the FAA agrees with commenters that use of the term “operator” in this rule could be confusing.” (emphasis mine). | ||

|

This is What a 107 Remote Pilot Can Log, But Is NOT Legally Required to & Really Does Not Matter |

|||

| Remote Pilot in Command | 14 CFR 107.12 & 107.19. | Applicable only to unmanned aircraft systems operations. |

Advisory Circular 107-2 at 4.2.5 says it nicely, “A person who holds a remote pilot certificate with an sUAS rating and has the final authority and responsibility for the operation and safety of an sUAS operation conducted under part 107. |

Recreational Drone Operations

A recreational drone operator cannot accurately rely on memory to determine when to change out batteries or propellers. Additionally, memory is a poor way to recall if preventive maintenance checks were done.

One can argue that flying a drone over and over again without logging the time the propellers have been used to be “careless and reckless” which is contrary to the Academy of Model Aeronautics Safety Code and the Drone Users Group Network Safety Guidelines. RCAPA’s general safety guidelines require that the drone be “airworthy” prior to flight. A logbook is a reliable way to determine time on properly for a drone operator to make a decision on the airworthiness of the aircraft.

Whether the above argument holds any water in a court of law is another discussion but this is more food for thought than listing potential arguments the FAA might throw at a recreational operator.

Commercial Drone Operators (Part 107).

Section 107.49 says:

Prior to flight, the remote pilot in command must . . .

(c) Ensure that all control links between ground control station and the small unmanned aircraft are working properly;

(d) If the small unmanned aircraft is powered, ensure that there is enough available power for the small unmanned aircraft system to operate for the intended operational time; and

(e) Ensure that any object attached or carried by the small unmanned aircraft is secure and does not adversely affect the flight characteristics or controllability of the aircraft.

How can a remote pilot comply with 107.49(c)-(e) if the remote pilot is not logging aircraft problems and maintenance? The FAA said it nicely in Advisory Circular 107-2, “Maintenance and inspection record keeping provides retrievable empirical evidence of vital safety assessment data defining the condition of safety-critical systems and components supporting the decision to launch.”

But here is the problem with drones, they are aircraft, but the drone manufacturers don’t treat them like aircraft. We don’t have any warnings being issued on certain parts like we have with the airworthiness directives in manned aviation. Yes, GoPro did a recall because of their batteries. The technology changes so much that the mean time between failures is not known for many parts of the drones. People just buy the Phantom 4 before the Phantom 2 or 3 broke. No one is sharing the data of the aircraft failures. Why would you want to and be called an idiot on the internet? So really any preventative maintenance being done, while appearing safe, is really going to be just best guesses.

Section 107.7 says, “A remote pilot in command, owner, or person manipulating the flight controls of a small unmanned aircraft system must, upon request, make available to the Administrator: . . .(2) Any other document, record, or report required to be kept under the regulations of this chapter.”

If you study Part 107 carefully, you’ll notice no log books are required to be kept; however, if you obtain a Part 107 waiver, the waiver requires the responsible person to have documented training the remote pilot in command and visual observer have received and that documentation must be available upon request from the FAA. This is what section 107.7 means by “Any other document, record, or report required to be kept under the regulations of this chapter.”

Reasons Why You Should Have a Drone Logbook

Legal Compliance. You might need to document training received for some waivers. Additionally, you might want to log aircraft maintenance to prove that you attempted to maintain the aircraft in an airworthy manner.

Marketing. Showing a completed logbook to a potential customer is a great marketing point. Like the old adage, “A picture is worth a thousand words,” a good logbook is worth a thousand flights. You can quickly demonstrate your flight experience by flipping through the pages. Furthermore, a well-kept and orderly logbook gives the impression that you are a professional.

Insurance. When you apply for insurance, they will ask you to fill out a form asking for all sorts of information. A logbook will assist you in filling out the form so you can receive the most accurate quote.

Maintenance. You cannot accurately rely on your memory to recall if you did something or not. Has that problem you observed gone away? Is it getting worse? Logging helps you notice trends and also allows you to rule out certain things when hunting for the cause of a problem.

Paper vs. Electronic Drone Logbooks

- Paper Drone Logbooks

- Fixed costs (unless you go through paper like crazy)

- No battery, no software, no firmware, no bad cell reception.

- If you are investigated, whoever is investigating is going to have to obtain the logbook itself as opposed to just subpoenaing the electronic logbook company to turn over all your info.

- No data theft.

- Some countries require paper logbooks.

- It is easier to allow a potential client flip through the pages than reading on your small cell phone with greasy smudge stains.

- Harder to “cook the books” with paper.

- Easier to transfer to another person who purchases a drone from you.

- Electronic Drone Logbooks or Drone Logbook Apps

- Totaling up the numbers is soooo much easier.

- Accurate total numbers.

- Less time spent on managing the logbooks.

- You can customize these as you need.

- Some plans have monthly fees.

- The data is less likely to be lost compared to a paper copy which has to deal with fire, flood, hurricanes, bad memories, etc.

- You can have data breaches.

- Law enforcement or personal injury attorney can subpoena the records from the database.

What Drone Logbooks Are on the Market?

Drone Logbooks Apps

Here are the more popular electronic drone logbooks. Some allow you to log pilot experience as well as aircraft time and maintenance. Most have a basic free version and the availability to add plans with extra features for a price.

- http://www.hoverapp.io/

- https://kittyhawk.io/

- https://www.dronelogbook.com/homePage/index.php

- https://airdata.com/

Paper Drone Logbooks

Here are the more popular paper drone logbooks.

- Commercial UAS Logbook 2nd Edition | Checklist | Maintenance Record

- ASA UAS Operator Logbook

- UAS Pilot Log Expanded Edition

- Drone Operator’s Logbook

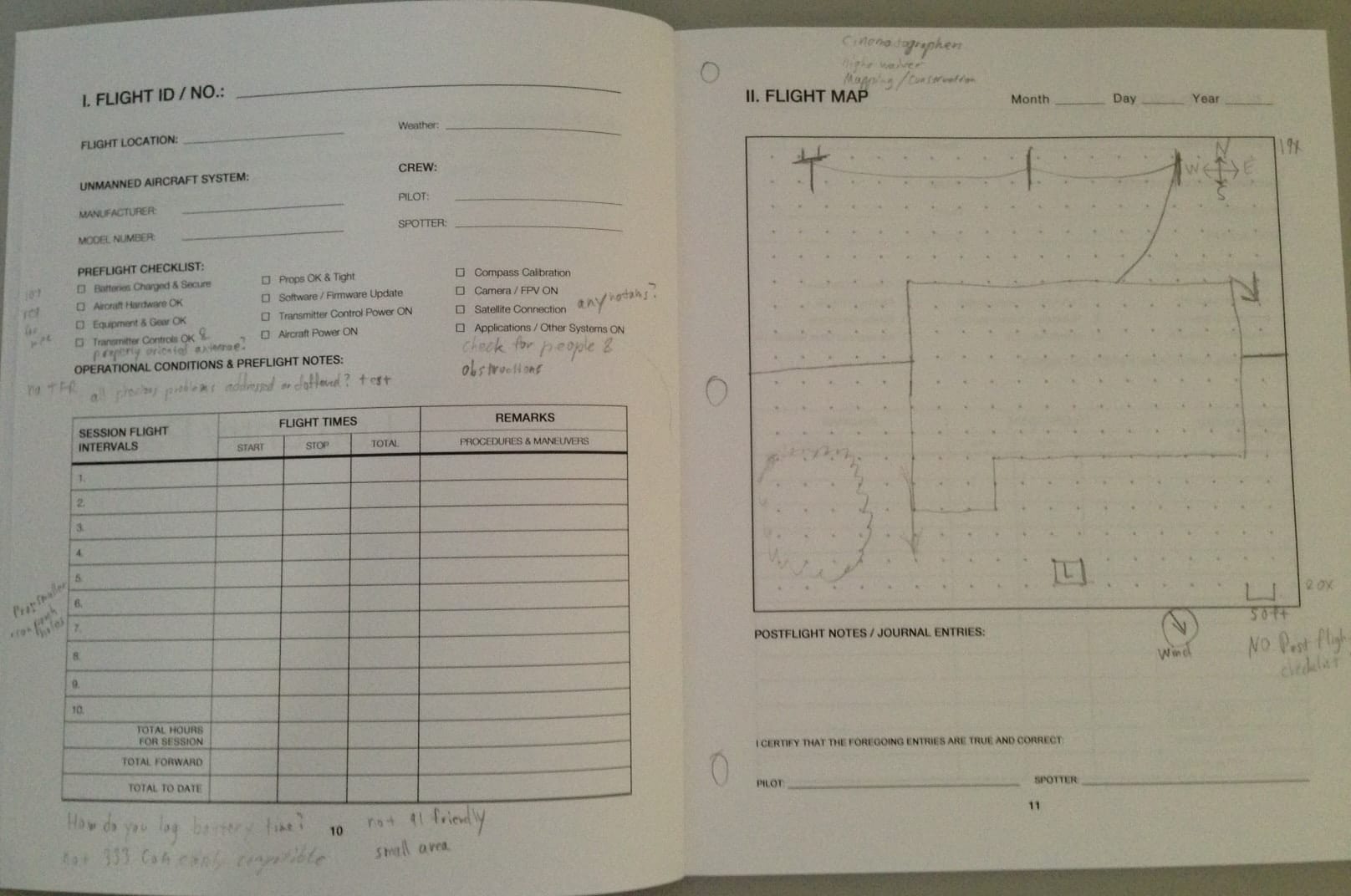

Review of the 3 Most Popular Paper Drone Logbooks on the Market

ASA’s The Standard UAS Operator Logbook

Pros:

- Compact.

- Hardcover so you can easily write in it.

- You could use it with a Section 44807 exemption because it is 61.51(b) compatible.

Cons:

- Some of the columns don’t make sense. For example, there is a “to” category and a “from” category. We are flying drones here guys. We don’t fly these anywhere else but right where we are standing. Another example is that there is a column for rotor, fixed wing, and a blank column. What in the world would you put in that blank column? Powered lift or lighter than air? Another column says instrument time.

- Small so you can’t write a lot of information in it.

UAS Pilot Log Expanded Edition

Pros

Pros

- It has this cool graph on the side. This is great for sketching things out. But you could just get regular paper and sketch things out if you need.

- There is an “eh ok” checklist built into every page.

- The gutter in between the pages might allow for it to be hole punched.

Cons

- It does not have rows or columns for the 61.51(b) elements. While 61.51 isn’t a standard for 107 or 44809 flyers, if you choose to adopt it, you’ll have to remember to put things in.

- There are not many columns to log different types of time.

- It has a pre-flight checklist but no post-flight checklist.

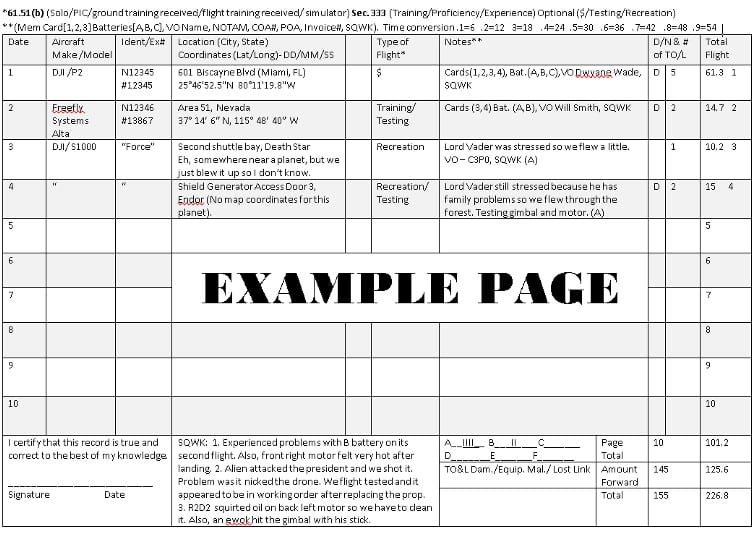

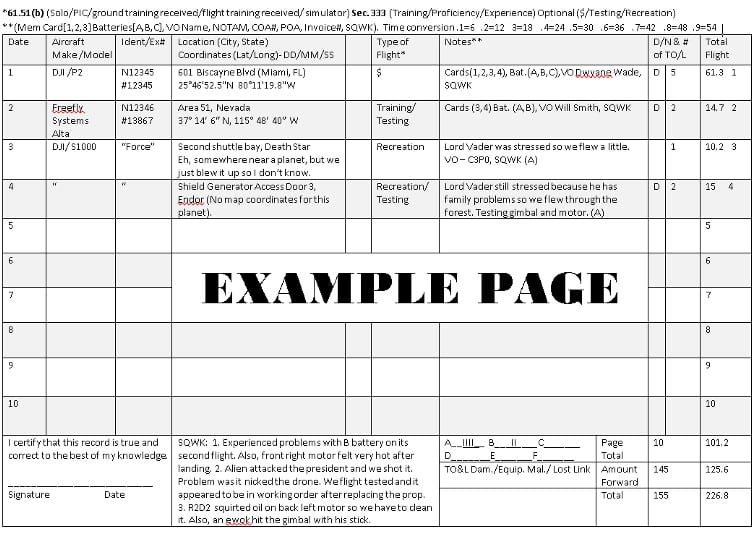

Drone Operator’s Logbook

- 61.51(b) elements are included in case you want to adopt this standard.

- You can log battery discharges right on each page.

- There is a TON of room on each page. You can easily log all your notes. Since it is also large, you can get regular writing paper and sketch out the job sites and then staple them to the page where you logged the flight.

- This logbook is large enough to also double as a maintenance logbook for your aircraft. When you make any repairs, staple in the receipts and make detailed so you can better diagnose problems or obtain a higher resell value for the aircraft because you can prove what was done to it. I would suggest if you want to use it as a maintenance logbook, that you buy a separate logbook just for the aircraft in case you fly multiple aircraft.

- Each page has a “cheat sheet” of things to jog your memory on what you might want to log on each line.

- It is a softcover so writing might be difficult.

- It is the largest of the logbooks (but you get a lot of room to write). It might be difficult to fit into a plastic sleeve that would fit in a 3 ring binder. However, I think the way around this is to just buy one of the plastic 3 ring expansion envelopes like this one.

- Some have complained that the gutter is too small which makes it difficult to hole punch the logbook.

If you want, you can just download the template of my logbook below and make your own! The benefit to buying it online is it saves on printing.

How to Fill Out My Drone Logbook.

Starting at the top, there are two rows with asterisks which are references for the Type of Flight and Notes sections. There is also a handy time conversion.

DATE: The date of the flight.

AIRCRAFT/MAKE & MODEL: Put the make and model of the aircraft.

IDENT/Exemption #: In this column, you can put the registration of the aircraft. You can also put in an exemption number if you want.

LOCATION. Some blanket COAs reports must list the city/town, state, and coordinates in decimal, minute, second format, (DD, MM, SS.S) N (DD, MM, SS.S) W, in the COA reports. Tip: Open up the iPhone compass app and it will display the GPS coordinates in the proper format at the bottom of the compass. 107 remote pilots or 44809 recreational flyers are not required to log this but may adopt to.

BLANK COLUMN. If you are operating under an exemption, check to see if you need to track your plan of activities (POA) submissions and NOTAM filing. You can also track invoice number, the pre & post voltage of batteries, takeoff or landing damage, equipment malfunctions, or lost link events.

TYPE OF FLIGHT. 61.51(b) lists terms like solo/pilot in command/flight, ground training, training received, or simulator training received. Notice the * reminds you to look at the top of the page for suggestions. 333 exemptions allow logging of (training/ proficiency/ experience). Optional entries could be ($/testing/recreation).

NOTES. Here are some suggestions: memory cards [1,2,3], batteries [A,B,C], the name of the visual observer (“VO”), NOTAM filed, the ID of the COA you are flying under, did you file the plan of activities?, Invoice #, pre/post voltage on the batteries, and SQWK (which means you documented in the SQWK section the problems and fixes).

D/N. day or night? # of TO/L. Number of take-offs and landings (hopefully they are the same number :) Some COA reports want “Number of flights (per location, per aircraft)”

Total Flight. Use a new battery for each line and enter the time after each flight. A convenient list of numbers is located on each page to help determine the most accurate entry. .1=6s .2=12s .3=18s .4=24s .5=30s .6=36s .7=42s .8=48s .9=54s For each battery, make sure you log cycles at the bottom with tick marks. This way you can keep track of when to fully discharge the drone battery based upon the manufacturer’s recommendations.

SQWK. Squawk section where you list any issues you discovered during flight. Instead of putting all of this in the notes section, just write “sqwk” and you’ll know to look at the bottom. In that section, You look for the number corresponding to the line number because all of the squawks go into the bottom box.

You can keep track of firmware updates by listing them below the battery section.

When you are finished with a page, add all the numbers up, sign the page, and cut off the corner of the page. This makes it easy to find the most current tab using your thumb.

Conclusion

I would highly suggest you do not just go and do nothing after reading this. You should log your flights to track any maintenance that needs doing as well as collect data to know when you need to change certain parts or the entire drone.

Get a logbook, a piece of paper, a Word document, one of the logbooks mentioned above, or anything! Just do it now. Don’t push it off. You won’t do. Start doing something. Today.

Stay safe. :)